How Women Bootleggers Dominated Prohibition

Did you know during Prohibition women were stellar bootleggers?

It’s true. When writing “Whiskey Women,” I concluded women bootleggers were more effective than men, because many states had laws that made it illegal for male police officers to search women. Back then, it was considered insulting to accuse a woman of such a dastardly crime.

Women bootleggers would hide flasks, even cases, on their persons and taunt male police officers. “A painted-up doll was sitting in a corner. . . . She had her arms folded and at our command she stood up. But then came the rub. She laughed at us . . . then defiantly declared to bring suit against anyone who touched her,” an unnamed Ohio “Dry Agent” told the Hamilton Evening Journal in 1924.

The alcohol smuggling syndicates took advantage of these legal loopholes, recruiting women into their ranks. Even if the gangs didn’t hire women bootleggers, they hired them for ride-alongs to reduce searches and robberies. “No self-respecting federal agent likes to hold up an automobile containing women,” according to the Boston Daily Globe.

The government feared women bootleggers outnumbered men five to one.

And frankly, bootlegging was good money with little punishment. In 1925, a Milwaukee woman admitted to earning $30,000 a year bootlegging. She was caught and fined $200 with a month’s sentence to jail, netting $29,800 for the year. Denver’s Esther Matson, 22, was sentenced to church every Sunday for two years after her bootlegging trial in 1930. Even President Warren G. Harding pardoned a Michigan woman bootlegger, and Ohio governor Vic Donahey commuted a woman’s sentence to five days.

It seems as though the court system and politicians just didn’t have the stomach for putting mothers and grandmothers behind bars. Most women were earning money just to keep a roof over their family’s head and food on the table. But there were some pistol-packing ladies who commanded empires.

These profiteer bootlegging women had cool nicknames, such as the Henhouse Bootlegger, Esther Clark, who stored liquor in her Kansas chicken coop; Moonshine Mary, who was convicted of murder for killing a man with bad liquor; Texas Guinan, aka Queen of the Night Clubs; and my favorite, Queen of the Bootleggers.

In 1921, federal authorities found $5,000 in bootlegging cash on Mary White, a stout woman with a “swarthy” complexion and missing front teeth. After sentencing, the press asked her if she was indeed the Queen of the Bootleggers, to which she replied: “I wish the hell I was.”

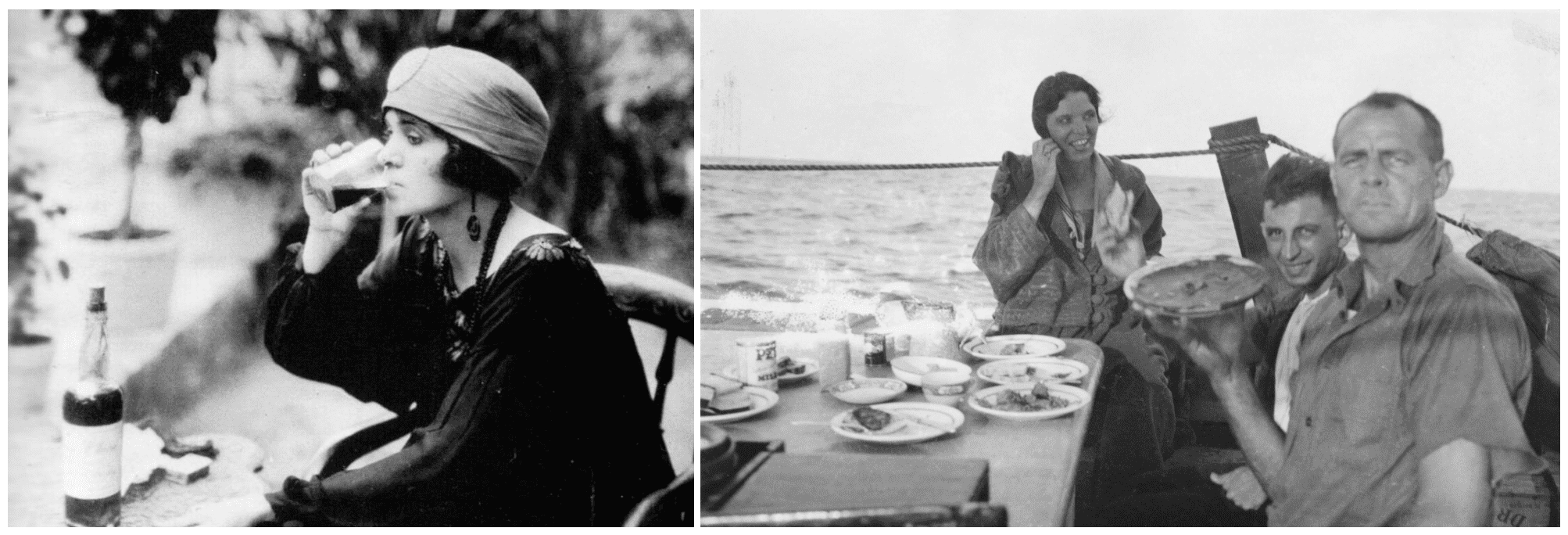

However, the greatest female bootlegger was Gertrude “Cleo” Lythgoe, a legitimate licensed liquor wholesaler in Nassau, Bahamas. A majestic-looking woman, Cleo was mistaken for Russian, French and Spanish, but she was American with ties to a British liquor distributor.

When Prohibition became law, she moved to the Bahamas and used her Scotland connections to import the best Scotch. In the Bahamas, this liquor was loaded on the boats of The Real Bill McCoy (who now has a rum named after him) and brought into the U.S. liquor supply. But, Cleo eventually moved into commissioning her own boats – that’s where the money was, after all. Bootlegging also came with greater risk.

Cleo became a target of the U.S. authorities and was even strip searched by a female officer at a port. But, unlike the other so-called Queen of the Bootleggers, Cleo loved the limelight and became a true media darling with newspapers from Jamaica to New York publishing her photo. Men fell in love with her and sent “love letters” to the newspapers. An Englishman, who simply signed “One Who Loves You,” wrote: “I only wish you lived in England. I would marry you, as a home life would be far more suitable for you than your present occupation.”

The Wall Street Journal estimated she was worth more than $1 million, but nobody really knows. Cleo was cryptic and never incriminated herself about her illegal dealings.

That’s the thing about women bootleggers. While the men were brash and loud, killing whoever got in their way, most women were swift and rarely talked.

It just goes to show: Women can keep secrets better than men.

About Fred Minnick

Wall Street Journal best-selling author Fred Minnick writes about drinking for a living. How good is that? Seriously, he wrote THE history on “Bourbon,” THE tasting guide on Bourbon in “Bourbon Curious,” THE book on rum in “Rum Curious” and important histories/tasting journeys in “Mead” and “Whiskey Women,” most of which are available in audiobook form through Audible. When he’s not writing books, he writes for Whisky Advocate, Whisky Magazine, and Covey Rise; or he’s serving as the Bourbon Authority for the Kentucky Derby Museum or curating the Bourbon lineup for the acclaimed festival Bourbon & Beyond. He’s also the editor-in-chief of Bourbon+. Let’s face it, Minnick often says, “I’m living the dream.” Unlike many of us who say that, he really is. Visit FredMinnick.com.